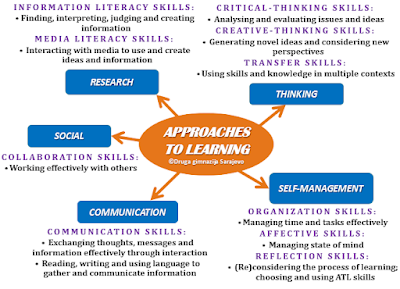

The school where I currently teach Latin is an IB World School, as was the one where I spent the most recent 23 years of my career. You can read more about the International Baccalaureate program on our website, but the aspect of IB on which I want to focus is called ATL, Approaches To Learning. One handy graphic lays out the ATLs like this.

An argument can be made, quite easily in fact, that these approaches to learning, while displayed here in somewhat new packaging, have in fact formed the basis of good teaching and learning for a long, long time. Because that is true, I have found that a project I have for many years assigned to Latin II students fulfills this model of instruction quite nicely. Or perhaps I should say that this model matches well with a meaningful project my students have regularly pursued.

After spending quite a bit of time reading in Latin the war writings of Julius Caesar in his campaigns against Gaul, the students choose partners (social) to work together to explore more deeply some aspect of the ancient Roman military. They must pick an issue or problem the Roman army of the 1st century B.C. would have had to address and then find out how the Romans actually handled it (research, communication). They must work together (social) to analyze (thinking) how well the Romans handled it given the resources available to them, and they must devise an alternative solution (thinking), one not necessarily better, but at least different, that the Romans could have employed, again given only the resources available to them. They have time both in and out of class to complete this, and I frequently use guiding questions to help them maintain their focus (self-management). Finally, they must present their findings and alternative solutions to the class (communication). The fun part, of course, is in their sharing of items they have made to illustrate their work, but more on that below.

Several years ago I co-hosted a podcast with Michigan Teacher of the Year Gary Abud, Jr. In one of our episodes, we spoke with Dr. Bernard Barcio, himself an Indiana Teacher of the Year and a 44-year veteran of high school and university classrooms. He talked about his decades-long project of guiding students in the construction of catapults, an effort that gained annual attention in the national news and that has been chronicled with archival video here. As we discussed in that podcast, such an approach to education grew to take on the name "project-based learning," although when Dr. Barcio began it back in the 1960s, it carried no such appellation. It was merely good teaching.

I am pleased, of course, if something I do in the classroom checks the boxes of the IB approach to learning. We are, after all, an IB World School. Yet what I, and I think the International Baccalaureate Organization itself, would argue is that this approach is simply about helping students make the most of their learning, regardless of what name the approach goes by.

What follows are pictures from this year's Caesar projects by the Latin II students at Guerin Catholic High School.

|

| On group recreated testudo, the tortoise shell formation of the Roman army. |

|

| Another group baked buccellatum, the hardtack eaten by soldiers. Yes, with jaw-breaking effort, I ate one! |

|

| One group crafted a Roman gladius from wood. |

Some may wonder why, in the age of electronic technology, my students create old-fashioned posters of the information. Some of my other projects do indeed ask students to present using electronic technology, but this project allows me to display student work in the hallway. Not only does this affirm the value of their work, but it allows other students to see the kinds of things we do in our classes, perhaps giving them something to look forward to when they reach Latin II.