|

| St. Jerome Translating the Bible |

They say that people who live in glass houses shouldn't throw stones, and since I am working on my own translation of Vergil's Aeneid, it may be ill advised for me to offer the scathing critique I am about to put forth here. On the other hand, sometimes a child needs to shout, "The emperor isn't wearing any clothes!"

The Whys of Translation

Why do we translate words from one language into another? The most obvious reason is to make ideas in one language accessible to those who cannot understand that language. There are innumerable ideas in poetry, philosophy, theology, history, science, mathematics, law, and all types of literature that people want to share and explore, and it is not possible or reasonable for everyone who is interested in those ideas to become conversant in the languages in which they were originally written. A person may master several languages, but even the most multilingual among us will be not be literate in all of them.

Another reason to translate is because translation itself is enjoyable and can be a work of art per se. The King James translation of the Bible is widely acknowledged as one of the most elegant works in English, and even though Richard Bentley did not think Alexander Pope's translation of Homer's Iliad was up to the mark, he conceded that it was "a pretty poem." My own efforts to translate the Aeneid are akin to climbing K2. There certainly is no need of another English Aeneid, for we have a full one hundred since the first in 1513. I simply want to do it. I have no delusion that mine could sit on the same high shelf as that of Dryden or Fitzgerald, but I have more fun translating than working the New York Times crossword, and the Aeneid is a really good story.

The Hows of Translation

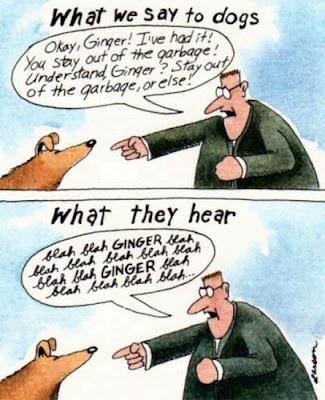

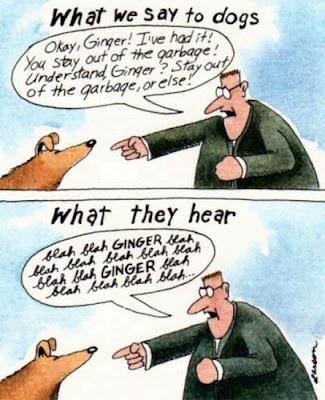

How does one go about translating a work from one language into another? A blog post is not the place to work through the ins and outs of translation theories, and they can drive a person close to insanity. Do I translate word for word? Even then, what does that mean? If a word means a canine animal, should I write "dog" or should I choose "puppy?" Must I keep the words in the same order as the original? There may be a particular sense expressed in that order, but when it is retained in English the result may sound like something from Yoda.

This takes us back to the first reason for translation. One method, or at least its results, may become outdated. For all its beauty, the King James translation of the Bible can be downright unintelligible to some today. It was published in 1611, and more than a few things have changed about English between then and the 21st century, hence the offering of sixty-two English versions on

Biblegateway.com.

And this leads us to the translation that I want to discuss here.

One That Cruncketh in Howling

A good friend recently emailed me a blurb about

Scot McKnight's

forthcoming translation of the New Testament. After a brief glance at the preview, I replied that it might be the most godawful thing I had ever seen. It reminded me almost immediately of one of the most mocked and reviled works in all of English translation, the 1582 attempt at the

Aeneid by

Richard Stanyhurst. Filled with grotesqueries like "her burial roundel dooth ruck, and cruncketh in howling," his efforts to produce English quantitative poetry like that of the Romans forced him into infelicities of expression and the use and spelling of words not current in his time. One of his phrases, however, could be used to describe what we have with McKnight's work, "darcklye bemuffled."

McKnight says of his guiding principle in translation,

"The basic theory at work in this translation can be summed up in these words: literal, chunky, sounds-more-like-Greek than standard translations (nothing against them), transliteration of names and places (like The First Testament), and somewhat disruptive for those who are familiar with their Bibles." Let's take a look at what this means.

Matthew 1:18

The genesis of Yēsous Christos was this: His mother, Maria, being engaged to Yōsēf, before they had assembled . . . she was found having a child in her womb of the Holy Spirit.

McKnight has transliterated the names from Greek into English letters, just as he said, and he held more closely to the Greek word order and syntax than most English versions, but to what end? The verb he translates as "assembled" is συνελθεῖν, which means any of the following: come together, assemble, meet, have dealings with, be united. Regardless of the theology you hold on the relationship between Mary and Joseph, "assembled" is simply ridiculous here. Why not say "came together?" "Assembled" has too many connotations in 2023 that just don't work in this instance. We use the word to describe putting together a child's toy on Christmas Eve or the coming together of a group of people. We do not use it to describe any action performed by only two.

Matthew 2:8

Whenever you find, declare to me so I also, going, may bow down to him.

The odd syntax here is quite common in Greek and Latin. The present participle "going" that modifies the pronoun "I" is usually rendered into some sort of clause in English, like "so I also may go and bow down." Keeping the Greek syntax in English reminds me of the famous story, often attributed to Churchill, about the man who was challenged on the correctness of his speech when he said, "That is something I won't put up with." The rule was often taught not to end a sentence with a preposition, so the man showed the absurdity of that by replying, "That is something up with which I will not put." Does McKnight's rendering follow accepted rules of English grammar? It does, but at the cost of wrenched and jarring syntax.

You may have thought I misquoted his line, for the expression "whenever you find" seems to want a direct object. Both Latin and Greek are okay with this, but English is not. The King James committee that published the Authorized Version in 1611 was so scrupulous as to put in italics words not in the original languages but that were necessary for English sense. Those translators rendered this as "and when ye have found him." I cannot see such torturing of English to imitate Greek as yielding anything other than frustration on the part of the reader.

Matthew 3:1, 13-14

In those days Yōannēs the Dipper [John the Baptist] arrives announcing in the wilderness of Youdaias.... Then Yēsous arrives at the Yordanēs from the Galilaia [Galilee] to Yōannēs to be dipped by him. But Yōannēs was preventing him, saying, “I have a need to be dipped by you, and come to me?”

The use of the present tense "arrives" in these verses is accurate and could even be justified in its retention if the effort is to make the narrative vivid. The historical present does just that. But referring to John the Baptist as Yōannēs the Dipper is beyond absurd. Actually, it may only be absurd. Making John say, "I have a need to be dipped by you" is beyond absurd.

The root verb of "dipper" and "dipped" in this translation is βαπτίζειν, a word meaning such things as "to plunge," "to be drowned," "to dip," and "to dye." Whichever definition you choose, you will be setting up a theological debate about baptism by sprinkling or immersion, but that is not the problem here. "Yōannēs the Dipper" simply sounds ridiculous, and while that may not sound like much of an objection, it is. When we use the word "Dipper" in its capitalized form in English, it invariably calls to mind the constellation called The Big Dipper. The phrase "John the Dipper" cannot help but summon images of Jack the Ripper, a rhyming phrase of the same number of syllables and the same rhythm. However accurate the word "dip" may be in this context, it carries too much other freight to be effective here. As for "I have a need to be dipped by you, and come to me," I can only assume this is a typo, since the Greek verb for "come" is not only second person singular, "you" in English, but even includes the second person pronoun σὺ, as if to emphasize "you."

You can read most of McKnight's translation of Matthew here, but you get the idea. So, why am I displeased with this work? It has to do with the reason McKnight had for translating. He says on his website, "Yes, I use some nonstandard translations of terms with which we are so familiar we don’t even see the words! Our prayer is this translation will slow readers down to hear the NT afresh." This is a laudable goal, one more worthy than my own of mere personal pleasure in the act of translation. Unfortunately, this translation misses the mark. The effort to be "literal," "chunky," and "more-like-Greek" has resulted in English that at times is merely awkward and at others nearly unreadable. If the goal is to slow readers down with a Greek-like translation so they can consider afresh passages that have grown dull through familiarity, there is a better way to go. Interested readers can learn Greek. The Greek-like version of McKnight is more akin to the odd and stilted translationese of the secondary or undergraduate language classroom.

One blurb on McKnight's website reads, "Scot McKnight's translation of the New Testament takes us into the very world of Jesus and the apostles; it breathes the air of antiquity. Rather than try to make the New Testament too familiar, McKnight makes it sound foreign, like a distant land you are hearing about for the first time. The Second Testament is a monumental literary achievement that will enrich and excite readers for generations." Why? Why would we want an ancient work in modern language that sounds ancient? First of all, the perceived oddness in the target language is not at all what first century audiences would have taken from the New Testament writings. Read a passage from McKnight's translation of Matthew and you will experience jarring strangeness. A first-century, Greek-literate person reading that same work in the Greek that Matthew wrote would have experienced ease and familiarity, at least with the style of writing. The content, on the other hand, is jarring in the extreme, but that comes from the power of what Jesus had to say. The message is already challenging. What benefit is there to reading it in the "air of antiquity," especially when the message bore no such antiquity in the period when it was written?

What made Richard Stanyhurst's 16th century English translation of the Aeneid so execrable was that he was attempting to write in English quantitative meter. Simply put, the quantitative meter of Homer's Greek and Vergil's Latin is based on long and short syllables, a system that does not exist in English, the poetry of which is often based on accent. By forcing the English language into the syntax of ancient Greek, McKnight has unfortunately proven what Jesus described with another metaphor. "Neither is new wine put into old wineskins. If it is, the skins burst and the wine is spilled and the skins are destroyed. But new wine is put into fresh wineskins, and so both are preserved," (Matthew 9:17, ESV).

If the goal had been to play with the form of languages and experiment as a jazz musician might do, then we could look upon this with a degree of interest. Since the stated purpose, however, was to draw people into a fresh encounter with the word of God, this version must be seen as one that only darkens the glass through which we are hoping to see.